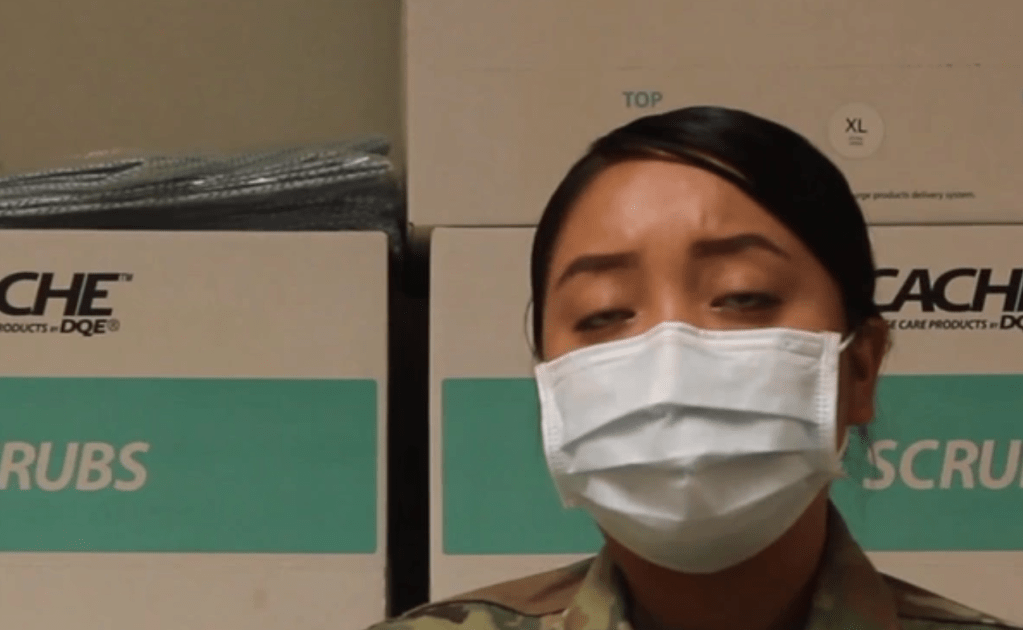

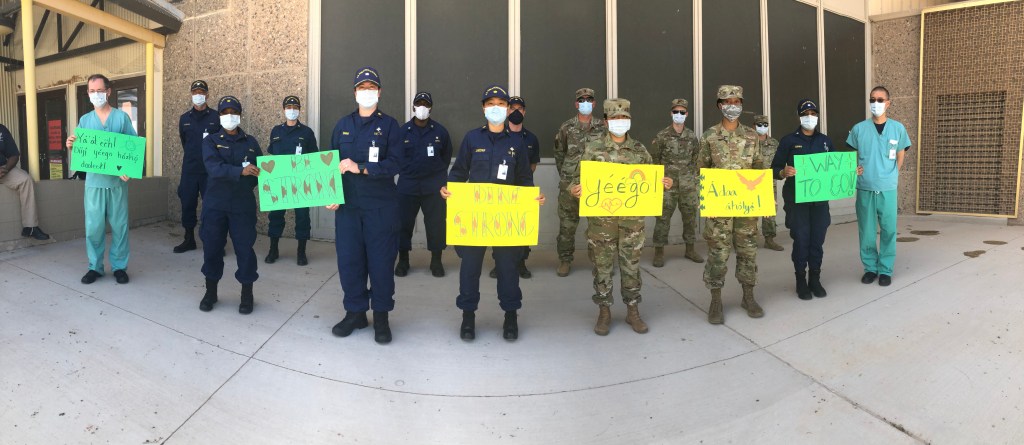

The most powerful interviews I performed took place in 2020 in Chinle Ariz. At that time Navajo Nation was being ravaged by COVID-19 and an old high school gymnasium was converted into additional hospital space. There were three National Guard soldiers with the ability to speak Diné and provide the required communication by the doctors from the National Institute of Health.

In the course of the interviews I found out how much it meant to the older tribespeople that the language was being spoken by a younger generation, and also how vital it was for the doctor to treat their patients.

First a brief history on the importance of the Navajo language, Diné. Wikipedia writes, “during World Wars I and II, the U.S. government employed speakers of the Navajo language as Navajo code talkers. These Navajo soldiers and sailors used a code based on the Navajo language to relay secret messages. At the end of the war the code remained unbroken.

“Were it not for the Navajos, the Marines would never have taken Iwo Jima”

Major Howard Connor, 5th Marine Division Signal Officer

“The code used Navajo words for each letter of the English alphabet. Messages could be encoded and decoded by using a simple substitution cipher where the ciphertext was the Navajo word. Type two code was informal and directly translated from English into Navajo. If there was no word in Navajo to describe a military word, code talkers used descriptive words. For example, the Navajo did not have a word for submarine, so they translated it as iron fish. These Navajo code talkers are widely recognized for their contributions to WWII. Major Howard Connor, 5th Marine Division Signal Officer stated, ‘Were it not for the Navajos, the Marines would never have taken Iwo Jima.’”

Meeting soldiers that are able to carry on the language that helped the United States win WWII in the Pacific is beyond an honor. To share their story, and a continuation of service to our nation and their people is humbling.

I wasn’t attached to any story or storyline on my drive up from Phoenix. I was going to be inquisitive and let the story develop.

In sprints, during the interviews this is the same mentality to have. Don’t be attached to the prototype, be curious about you’re about to find out.

In Sprint: How to Solve Big Problems and Test New Ideas in Just Five Days by Jake Knapp, John Zeratsky, and Braden Kowitz, they write, “people need to feel comfortable to be open, honest, and critical. So the first job of the interviewer is to welcome the customer and put her at ease. That means a warm greeting and friendly small talk about the weather. It also means smiling a lot.”

Building trust with someone you’re interviewing makes for a better interview.

“In the real world, your product will stand alone – people will find it, evaluate it, and use it without you there to guide them. Asking target customers to do realistic tasks during an interview is the best way to simulate that real-world experience,” writes Knapp, Zeratsky, and Kowitz.

Within the sprint it’s all about the feedback, it tells us the story of what works and what doesn’t. That comes out during the interview. The same happens outside of sprints, I ask questions and get feedback and the story emerges. I’m unattached to what the story is, but I’m invested in tell the best most accurate account that my interviewee has interested me with.

Leave a comment